To borrow some professional wrestling jargon: Wrestlers doesn’t quite “get over” as a “work.” More on that later. First, the setting of the new Netflix docuseries, Ohio Valley Wrestling (OVW), should be established.

Located at 4400 Shepherdsville Road in Louisville, Ohio Valley Wrestling is the latest in a long line of wrestling promotions that has called the Falls City home. In fact, pro wrestling in Louisville goes all the way back to the 1880s, when an up-and-coming athlete could challenge a wrestling champion to a match by posting an ad or writing a letter to him in the Courier Journal.

According to local pro wrestling historian and author John Cosper, even then the outcomes of those professional wrestling matches were predetermined. Promoters and wrestlers would work together and host matches, lasting several hours and containing multiple falls or rounds, like in a boxing fight. The parties would determine which side had received the most money bet by the later rounds, and then “decide the finish based on would could win the more money.” Even then professional wrestling was a “work.”

Over time, several independent promotions — a few homegrown, most produced by promoters from other wrestling territories — would pitch a tent in Louisville: from Heywood Allen’s Athletic Club of the 1930s–50s, which hosted matches at the Armory (now the defunct Louisville Gardens) and segregated matches at the Savoy Theater at 223–227 West Jefferson Street in Downtown Louisville (where Jim Mitchell, the “Original Black Panther,” made a name for himself) to Jerry Jarrett’s Memphis Wrestling of the 1970s–90s.

By the 2000s, when the business turned into a veritable monopoly run by World Wrestling Entertainment, OVW (founded in 1993) entered the spotlight as a farm league for the WWE. It developed talent like John Cena (known as the Prototype during his OVW days), Dave Bautista (Leviathan), and Brock Lesnar.

Today, the WWE is out of the picture at OVW. But one of the holdovers from those days, former WWE star Al Snow, has stayed in Louisville and is now the CEO and co-owner of the company. And that is where the action begins with Wrestlers.

The story finds Snow struggling to keep OVW in business. Enter Matt Jones and Craig Greenberg—the Kentucky Sports Radio raconteur and the mayoral candidate, respectively—who want to preserve a “Louisville Icon” in OVW and invest in the venture with Snow. Out of that relationship arises the most interesting, yet least developed, drama in the entire series.

Wrestlers fleshes out the life stories of many in the OVW roster. We witness the transformation of Kentuckian Haley James from problem child to antihero Hollyhood Haley J (Episode 5). We revel in the joy that Louisvillian Mike Walden takes in barnstorming for family and friends at Hillview Softball Field on Crestwood Lane as the babyface Ca$h Flo (Episode 3). We empathize with the struggle of Amanpreet Singh Randhawa (a.k.a. Mahabali Shera) to acculturate to the pro wrestling business in America and keep his integrity as both an athlete and an adherent Sikh (Episode 4). We even catch a glimpse of the inner life of Matt Jones, a self-confessed mama’s boy, as he takes his mom to her first live wrestling match in Harlan, Kentucky, during the Poke Sallet Festival (Episodes 3 and 4).

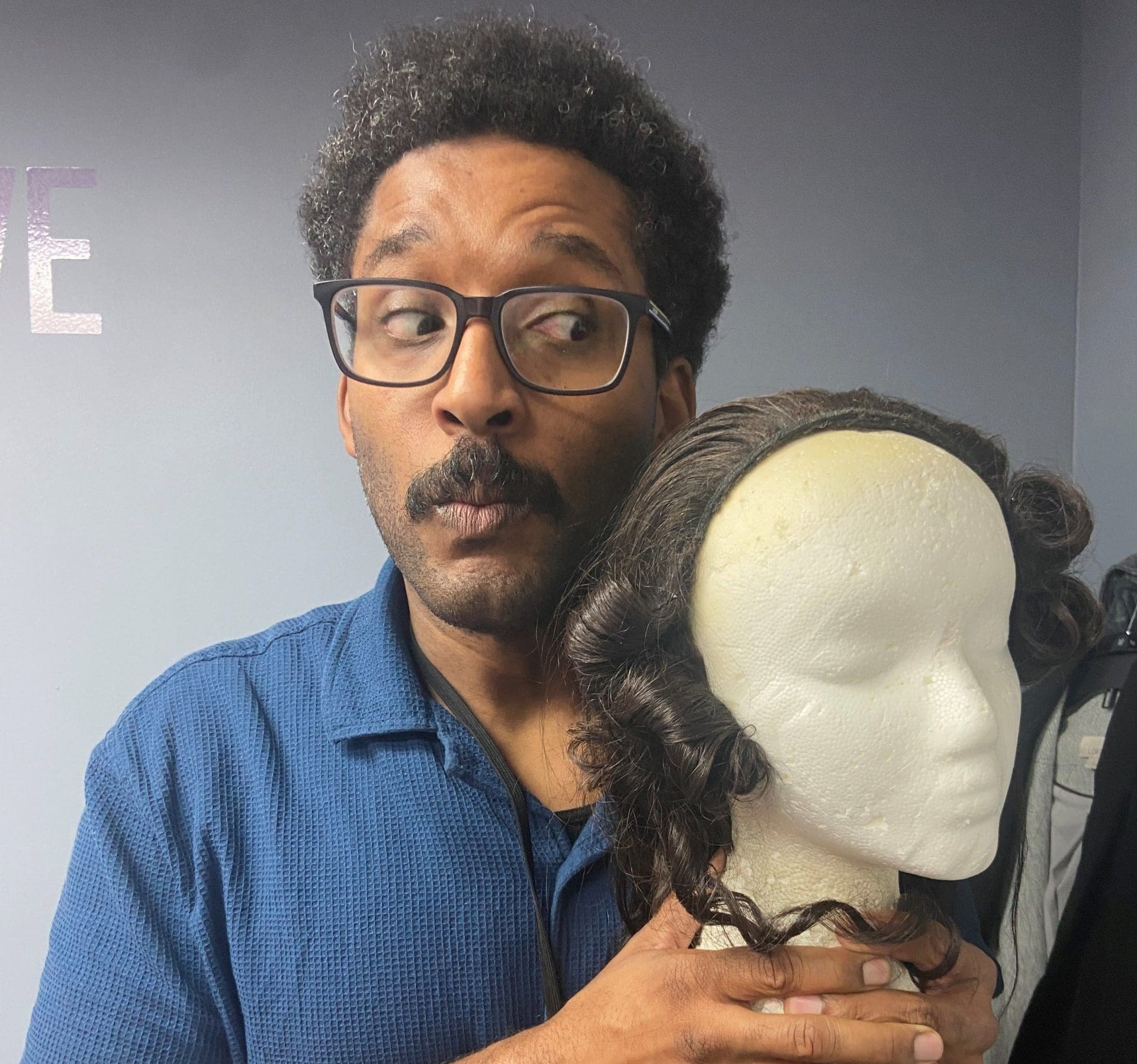

So, it comes as a surprise when so little of Al Snow himself is revealed in the series. Personally speaking, it would have been fascinating to witness Snow’s transformation from his days as an unabashed “jobber” in WWE in the 1990s—when kayfabe (think of it as pro wrestling’s Holy of Holies) was irrevocably torn asunder by incidents like “the Montreal Screw Job”, and Snow once wrestled his own mascot, a wigged Styrofoam head, and lost—to his role as a pro wrestling elder statesman, the grizzled stoic of Wrestlers.

To be sure, we are made privy to the vicissitudes Snow faces (“the @#$% sandwich” he calls it) in the business. He tries to keep the tradition of “physical storytelling” intact at OVW, while making compromises to Jones and Greenberg, who make constant overtures for better box office and more corporate sponsorships. He navigates the delicate balance of the locker room, where substance abuse and personality conflicts abound and threaten to derail Snow’s “picture puzzle” of a story for OVW. Snow confronts his own legacy as a wrestler and a storyteller. But, the transition — from jobber to sage — is missing.

That said, Snow’s old persona, the leader of the J.O.B. Squad, makes two outside-the-ring appearances in Wrestlers. It is at those moments when Wrestlers goes over from a run-of-the-mill docuseries into something that comes alive. It is those two instances that demonstrate that Wrestlers — to use late 1990s pro wrestling jargon — needs more head.

For more interesting Kentucky history content, subscribe to the Frazier Museum’s free newsletter “Frazier Weekly.”